John Beilein teams have never been renowned for their ability to crash the offensive glass. Last year the Wolverines jumped 100 spots in offensive rebounding but still ranked just 139th in the country and 8th in the Big Ten.

John Beilein teams have never been renowned for their ability to crash the offensive glass. Last year the Wolverines jumped 100 spots in offensive rebounding but still ranked just 139th in the country and 8th in the Big Ten.

Beilein has never been shy to share his philosophies on the matter. He would rather play steady transition defense than crash the offensive glass for an extra possession. That logic has largely been driven by the fact that Beilein has rarely had the personnel to justify crashing the offensive boards.

Michigan’s head coach is not unique in his thinking but Grantland.com’s Zach Lowe argues that he might be incorrect in his recent story ‘Party Crashers: Debunking the Myths of Offensive Rebounding and Transition Defense’. Lowe notes Gregg Popovich, Doc Divers, Mike Brown and Stan Van Gundy as highly regarded NBA coaches that share the same philosophy.

Lowe concludes that great offensive rebounding teams can be good, bad or mediocre transition defenses. There’s no correlation between the two statistics. Lowe’s study focuses on the NBA, mostly the Indiana Pacers and his results prove true in the college game as well. Picking up where Lowe left off, I crunched some numbers to look for a correlation between offensive rebounding and transition defense at the collegiate level.

I pulled every Division I team’s offensive rebounding percentage, points per transition possession allowed and percentage of transition possessions allowed to look for any correlation. Those three metrics give us: how effective teams are on the offensive glass, how effective they are at stopping transition offense and how often they give up transition possessions.

The first scatterplot below shows the percentage of transition possessions allowed against offensive rebounding for every Division I team last season. This graph looks for some correlation between how many fastbreak possessions a team allows and their offensive rebounding effectiveness.

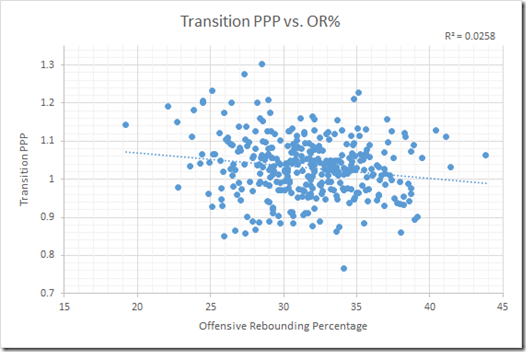

The next scatterplot compares points per transition possession allowed against offensive rebounding percentage for every Division I team last season.

Those charts tell us that there’s very little, if any, correlation between offensive rebounding productivity and transition defense (both quantity and effectiveness). There’s slightly more correlation in the first graph which makes sense. Conventional wisdom is that the more often you crash the glass, the more often your opponent will fast break.

The next graph, transition effectiveness, actually shows a very slight negative correlation, meaning that the better offensive rebounding teams actually do a better job of defending transition opportunities. This somewhat makes sense as these teams could have the best athletes, but the R-squared value of less than .03 tells us that this is essentially a random sampling of data.

The major caveat with this dataset lies on the offensive rebounding side of the equation. Offensive rebounding percentage measures how effective a team is at crashing the glass, it doesn’t say for certain how aggressive they are. One team could crash hard but not come up with many offensive rebounds, another team could send just one player but he grabs a team’s worth of offensive rebounds.

Studying offensive rebounding aggressiveness would require extensive film analysis, something this study did for the NBA. However, it’s a reasonably safe assumption to conclude that offensive rebounding percentage and offensive rebounding aggressiveness are fairly correlated.

The numbers very clearly support Lowe’s argument. There’s no correlation between offensive rebounding and transition defense on a broad level.

Rebounding, transition and Michigan

While there’s no correlation on a national scale, Michigan’s 2012-13 team was its best offensive rebounding team in the last three years. It was also Beilein’s worst transition defense team of the last three seasons.

The Wolverines allowed opponents to fast break on 13.4% of their offensive possessions – the sixth most allowed by any Big Ten school over the last three seasons. In the two years prior, Michigan allowed opponent transition possessions on 10.3% and 9.9% of their defensive trips – the two lowest percentages of any Big Ten school over the last three seasons.

| Year | Transition Poss% | Transition PPP | OR % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012-13 | 13.40% | 0.987 | 32.5 |

| 2011-12 | 10.30% | 0.972 | 25.8 |

| 2010-11 | 9.90% | 1.008 | 21.5 |

So the Wolverines went from being one of the very worst offensive rebounding teams and the very best transition defense to a decent offensive rebounding team and an awful transition defense.

Michigan’s numbers over the last three seasons demonstrate the very trend that this post set out to disprove. So what gives?

There are two probable explanations for this phenomenon:

- Michigan had an extraordinarily young and athletic team. The youth led to worse transition defense while the athleticism led to improved offensive rebounding.

- Michigan was had to be significantly more aggressive in its offensive rebounding approach to reach that improvement, and it paid the price for it with its transition defense.

I tend to side with number one. Michigan had a young team and young teams can lack the discipline to play great transition defense.

If number two were the case, it was a mistake in philosophy. The numbers show that the gain the Wolverines saw on the offensive glass didn’t match its loss in transition defense.

| Year | OReb Poss/Gm | OReb Pts/Gm | Trans Poss/Gm Allowed | Trans Pts/Gm Allowed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012-13 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 9.9 | 9.8 |

| 2011-12 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 7.2 | 7 |

| 2010-11 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 7.1 | 7.1 |

Michigan surrendered just under three points per game more in transition defense last season compared to the two seasons before but only saw a scoring increase of roughly half of that in second chance points.

Next Year

The good news is that the Wolverines should be able to improve their transition defense and their offensive rebounding without any drastic change in strategy. John Beilein has the league’s best offensive rebounder in his back pocket: Mitch McGary. Michigan doesn’t have to send more players to the offensive glass, it just has to send McGary.

McGary’s offensive rebounding rate of 16% ranked 10th best in the country and was best in the Big Ten. His production regressed to a degree in league play but with the opportunity to be a full time starter, his ability to impact Michigan’s overall offensive rebounding effort will increase significantly. With McGary in the lineup full time, Michigan could move into the top-half of the Big Ten in offensive rebounding for the first time since 2008.

The net-benefit of sending more players to the offensive glass might be limited unless the Wolverines move to a two big lineup. With McGary at the four and Morgan or Horford at the five, the intrigue of crashing the glass becomes greater. Morgan and Horford can both hold their own on the offensive glass and make an impact.

With McGary at the five, there isn’t really anyone else to send. Glenn Robinson III is a terrific athlete but he doesn’t necessarily have the temperament (or production) to justify crashing the glass every possession. Nik Stauskas grabbed 20 offensive rebounds total in his freshmen season and Caris LeVert, Zak Irvin or Derrick Walton aren’t going to make a great impact on the glass.

Michigan’s guards and wings need to figure out a way to fix the other side of the equation and shore up Michigan’s defense. Having the most efficient offense in the country last season masked a lot of problems but without Trey Burke and Tim Hardaway Jr. and with an extraordinarily young backcourt, the Wolverines can’t afford to do such a poor job of defending transition offense again this season.